Language is a Concept: Kao-Face

Language is a Concept: Kao-Face

Language is a Concept: Kao-Face

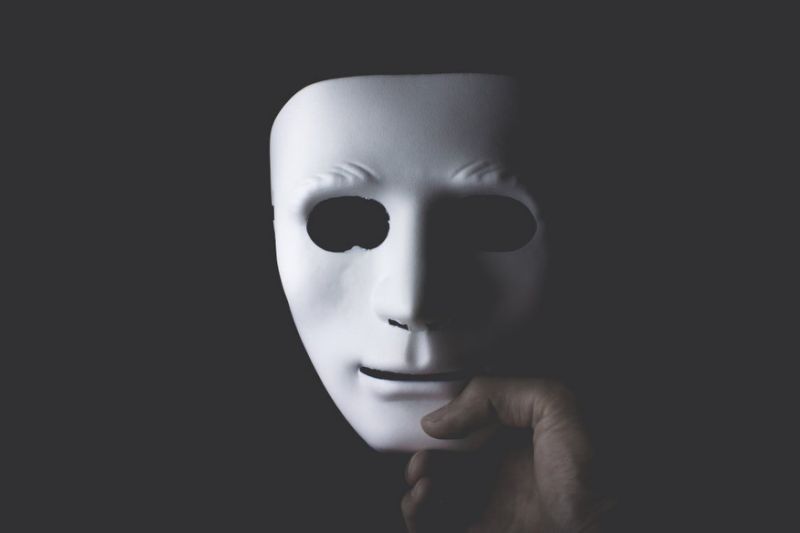

Like many things in Japanese culture, coming to an understand of key social concepts and the significance of their meaning to the Japanese takes intention and awareness to fully understand.

One must say gaining an in-depth understanding of “kao” or “face”, and the gravity of protecting one’s face is of paramount importance to successfully interacting with the Japanese.

Always keep in mind, Japanese people tend towards being very sensitive to insults, slights, smears, and slurs of any kind, including many things Occidentals would usually ignore or simply disregard.

In the realm of protecting one’s name, reputation, and even more so one’s very honour, Occidentals usually seem to have very thick skin, while the Japanese often seem to have no protective skin whatsoever.

This cultural element apparently derived from the fact that until modern times (post-1945), generally speaking the Japanese were not allowed to express individualism or one’s own preferences, except in ways that were traditionally sanctioned by society, meaning doing only things Japanese society approved of, and only then when they were done in the accepted Japanese way.

Remember, these centuries old customs and protocols are ingrained societal conventions, which are woven into the fabric of Japanese society from the start of one’s life.

Historically, one of the few meaningful things the Japanese had going for them was their “kao”, which means one’s reputation.

So one can say that losing face for the Japanese creates extremely grave situation for both parties involved.

And one can see why protecting and defending the dignity and honour of one’s family is so very important in Japanese society.

In times past, when one’s face was trod upon one was not only officially or formally allowed to complain, they could in many situations get even, including officially sanctioned attempts to kill the offender.

One only needs to look to Japanese history for countless accounts of sleight and revenge.

For certain, kao and shame are inextricably intertwined into Japanese culture, and still play a significant role in Japanese life today.

When dealing with the Japanese, for whatever purpose, one must keep the important cultural protocol of kao firmly in mind.

When it is impossible to avoid saying or doing something that is very likely to smudge the face of a person, you can mitigate its effects by apologizing in advance, or quietly discuss some issue away from the group where the recipient will not feel a sense of shame or a lose of kao among one’s group.

Perhaps other societies around the world can take the importance of kao as an example, and leave out shaming others all together.

Even better yet, if it is necessary to say something, do so in a civil manner where, instead of tearing it down society while creating disharmony and lose of kao, one can building the society up and strive for harmony amongst the people, wherever one may live on our shared earth.

Recent Comments